“His funeral would have pleased the Generalissimo. Even as a dead man, he possessed the power to kill people: during the funeral on March 9, 1953 in Red Square, hundreds of people were trampled or suffocated in the crowd.

But even camp inmates, whose lives the dead man had destroyed, whose futures he had robbed, whose families he had wiped out, declared slaves and brutes, banged their heads against bars and barbed wires in the deepest despair when they received news of the Führer’s death.” Haratischwili, Nino: The Eighth Life (For Brilka), p. 495

Basic information about the book The Eighth Life

Nino Haratischwili published her novel The Eighth Life (For Brilka) in 2014 with Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt.

This novel, recommended late at night by the rock singer of a bar in Tbilisi, who shares the first name with its author, is both a curse and a blessing. The words, chosen with care, continue to have an effect for a long time and sometimes haunt the reader’s dreams.

The plot describes the political history of Georgia from 1900 to the present and its effects on the population. In order to present the circumstances in a particularly impressive way, the author draws on the rise and fall of a family from Tbilisi (Tiflis) over five generations for direct comparison.

The structure of the book, which comprises 1279 pages, is divided into a prologue and eight chapters, seven of which are devoted to the female members of the family.

The last part consists of blank pages, because Brilka, the youngest descendant of the chocolate manufacturer with whom everything began, is still a blank page.

The lengthy and precise reproduction of the content is deliberately omitted, this can be found on the Internet enough.

A masterpiece – frightening and touching at the same time

So what’s so fascinating about a tome that tells of times long past and a small, beautiful country that, until now, has simply been overlooked by most people?

First, it is admirable to maintain an arc of suspense throughout the length of this massive book. Haratischwili captivates the reader to her narrative; there is never a dull moment. The abundance of characters, information and details in no way impedes the flow of reading; surprising twists and turns keep the reader in check, shimmying from one catastrophe to the next.

Good entertainment guaranteed

Again and again, despite all the tragedy, there are also witty remarks and passages as well as many interspersed quotes. Politicians such as Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Josef Stalin and Karl Marx, literary figures such as Anna Akhmatova, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov and Maxim Gorky, and musicians such as Leonard Bernstein, Billie Holiday, David Bowie and Bob Dylan have their say.

The ballet classes that Stasia continues to take even in her old age are just one example of how the female characters in particular have a high level of determination and willpower and never give up hope for a different life, which comforts not only the fated characters but also the reader.

Art in the form of music and literature is given a supporting role, as a force that manages to make the protagonists come to terms with traumatic experiences and still go on living. This is the case with Christine (opera), Stasia (dance) and Kitty, who rises to become a celebrated singer herself; Niza herself writes down the family history in order to create understanding for the past in herself and Brilka.

Haratischwili has succeeded in creating a work that makes the reader laugh, cry and think in equal measure, while still remaining entertaining on every page.

The personal narrative style of Nino Haratischwil

The narrative form additionally loosens up the novel. It is by no means an omniscient, uninvolved observer who relates the events; the author uses a character from her book to report on the past.

Because the narrator of the novel, Niza, has been told many of the situations described only orally, since she was not yet born or present herself, there are naturally gaps in her memory and ambiguities. Brilka is also frequently addressed directly. The use of a protagonist as reporter makes it easier for the reader to identify with her and creates closeness.

Closing gaps in knowledge

The Eighth Life functions not only as a literary work but also, as it were, as a lesson in history and political education, and it is never exhausting or intrusive.

The reader is told the legend of the creation of Georgia, is tutored in the matters of the First and Second World Wars, the Russian Revolution, the Prague Spring, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The most recent event is the mass protests in Tbilisi and Batumi in 2007.

The book is therefore a real treasure for readers who want to get into the history of Georgia or deepen their knowledge.

Nino Haratischwils escape into a foreign language

Nino Haratischwili uses the German language for the original version, which she learned at school, for her books. According to her own statement, she uses it as a safe refuge and to create distance. The power of language in the novel is impressive, every word is right and none is superfluous.

The author uses an elegant style of expression with long, melodious, sometimes terribly convoluted sentences, demanding undivided attention from the reader. The content is too important to be simply skimmed over; it is necessary to let every word have an effect in order to really understand the connections.

Expressions that are rather out of place in German literature (Trottel, Wampe) or foreign words (somnambul, Päderast) are also deliberately woven in, Haratischwili deliberately plays with different styles, which makes the reader stumble and pause for a moment.

As a native Georgian, the author has the courage to criticize politics and her compatriots and also strikes ironic tones.

Magic elements

The text can be understood in the tradition of Magical Realism, as evidenced by the leitmotif of hot chocolate, which, like a magic potion, is capable of bringing death and destruction upon the recipient.

In the Green House, the family residence, magic is also omnipresent.

“The plants sensed it and sprouted like crazy in the garden. Little by little, they invaded the house as well. Even the furniture began to make strange noises and all kinds of birds held their meetings in the attic. Butterflies and grasshoppers sought out the house, stray cats walked around the house, squirrels and martens were also spotted.

The house breathed a sigh of relief. It was bursting at the seams, shedding the strict corset that had enclosed it for years, it was beginning to come to life. Noisily, expansively, noticeably and visibly. Haratischwili, Nino: The Eighth Life (For Brilka), p. 525/526

The excursions into myths, history and art that are undertaken underline this impression and, together with the other fantastic elements, blur the line between reality and illusion.

Highly recommended reading

Nino Haratischwili’s book is an asset for a wide variety of audiences and, in any case, interesting for those readers who want to dare a look behind the scenes of Georgia.

It is a work that can trigger a wide variety of feelings in the audience, including trepidation, pity, or anger.

In the end, what remains is admiration for an artist who honestly and unembellishedly describes the horrors suffered by her homeland and its inhabitants, but who nevertheless does not allow herself to be robbed of her hope and, despite everything, looks confidently to the future.

Nino Haratischwili – Gifted storyteller and unsparing critic

Nino Haratischwili was born in 1983 in Tbilisi and grew up there, where she enjoyed intensive German lessons at school. Only the years between 1995 and 1997 were spent in Germany, due to the civil war that was raging in her home country at the time.

Already as a teenager she founded her own German-Georgian theater group. After completing her studies in film directing in Tbilisi, Haratischwili moved to Hamburg in 2003, where she studied theater directing at the Theaterakademie and now lives in Berlin.

She has directed world premieres in countless German theaters and has received numerous awards for her dramatic texts.

The first novel Juja was published in 2010 and was very successful. The first novel was followed by the short stories Mein sanfter Zwilling (2011), Das achte Leben (Für Brilka) (2014), Die Katze und der General (2018) and Das mangelnde Licht (2022).

The author has received several awards for her literary work, including the Berthold Brecht Literature Prize for her dramas and the novel Das achte Leben.

Most recently, Haratischwili was awarded the Carl Zuckermayer Medal in 2023 “for her services to the German language.” In her acceptance speech, the author included a great deal of personal information and was thus able, once again, to really move people.

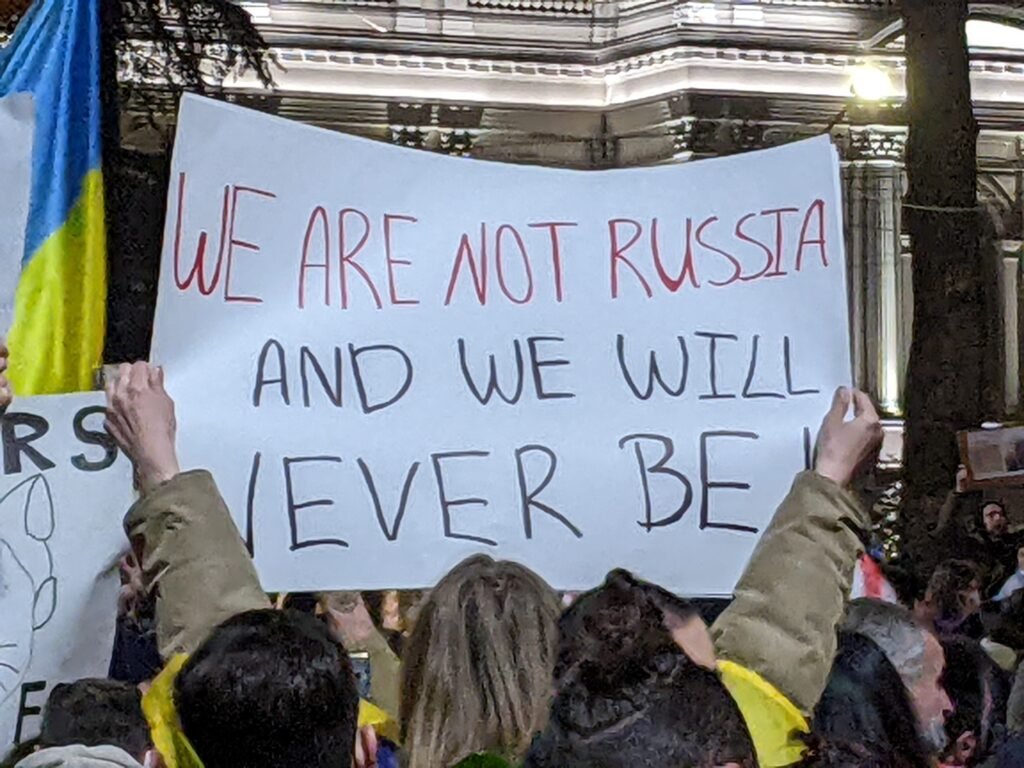

In her speech, Haratlschwili also talks about her personal experiences with the war, which she had to witness at first hand twice, and takes this as an opportunity to appeal for support for Ukraine and to thank her for her resistance.

Meaningful words

“Right now it is up to Ukrainians to risk their lives, and we can only be glad and grateful that we are lucky to be here. Only a vacation sometimes separates us from the war, from the horror, from the collapse of every civilizational blanket, which for some people is just a cover that can simply be pushed aside at will. For example, for the Russian president and his bloodthirsty entourage, which for twenty-three years has not had enough: of money, of power, of blood, of more territories to destroy and annex.

Two days ago, another Russian missile hit an apartment building in Dnipro, killing forty-five people. Just like that. From one moment to the next. This horror goes on and on and on, and this brave people stand firm, and how can I not be grateful tonight – to these people who have stood firm against this horror for over a year, who do not lose hope, and who remind us that we never want to go back: to tyranny and to dictatorship.

And so I thank every single person in Ukraine and elsewhere who is fighting against the return to the past from which we seem to learn so little.

And please let us not forget these people, let us also fight, with the means we have, let us not let this war become a background noise. Because these people need our help. And as a little tip to some cultural workers in this country: It’s easy to ponder peace and pacifism when you’re sitting in a nice old apartment with a noble glass of red wine in your hand. But when bombs start falling, and I say this from my own experience, it’s easy for, shall we say, more archaic feelings to come to the fore, feelings that are hard to reconcile with philosophical discussions about the senselessness of violence and the usefulness of powdered milk.”

The impressive acceptance speech can be read here in German.

The Eighth Life: Protest through art

Nino Haratischwili not only warns against Putin and new wars, but also loudly criticizes the abuses that still prevail in her home country.

In her works, she gives a voice to those who are still condemned to silence in Georgia.

Disadvantaged femininity in Georgia

Although the acceptance and equality of women in Georgia is publicly propagated and a woman, Salome Zurabishvili, has been steering the fate of the state as president since 2018, the reality unfortunately looks different.

It seems that Georgians have forgotten that it was a woman, Queen Tamar, who led the nation into the Georgian golden age many hundreds of years ago.

Even the statue of Mother Georgia, which towers imposingly and hugely on Sololaki Hill in Tbilisi, degenerates into mere decoration in the context of the current situation.

For patriarchy still prevails within Georgia, and this fact has become a matter of course for most of the inhabitants. Women are treated as secondary, oppressed and are often victims of domestic violence.

It is probably due to this injustice that Nino Haratischwili offers most space to female protagonists in her books.

Some female characters manage to experience freedom and healing even after all the blows of fate. Christine finally triumphs over her tormentor, Kitty finds a new home in the arms of Fred, and Stasia dances pas de deux until shortly before her death.

It is probably due to this injustice that Nino Haratischwili offers the most space to female protagonists in her books.

Some female characters manage to experience freedom and healing even after all the blows of fate. Christine finally triumphs over her tormentor, Kitty finds a new home in the arms of Fred, and Stasia dances pas de deux until shortly before her death.

Hate and exclusion

There is only one population group that is hit even harder and that is all those who belong to the LGBTIQ community.

Homosexuality has been legal in Georgia since 2000 (!).

Thanks to the powerful Orthodox Church and its influence, homosexuals, bisexuals and transgender people are still met with undisguised hatred and fall victim to daily hostility.

Again and again there are public attacks, not only in the course of the devastating riots during the Pride Parade 2021. Also then, besides right-wing extremists, high-ranking spiritual dignitaries were in the front line, set the rainbow flag on fire and actively participated in the violence.

Nino Haratischwili processes these impressions in her play Phaedra, in Flames, which is currently on the program of the Vienna Akademietheater, and reacts to them by changing the myth so that Phaedra falls in love with Persea instead of Hippolytus.

There is only one population group that is hit even harder and that is all those who belong to the LGBTIQ community.

Homosexuality has been legal in Georgia since 2000 (!)

Thanks to the powerful Orthodox Church and its influence, homosexuals, bisexuals and transgender people are still met with undisguised hatred and fall victim to daily hostility.

Again and again there are public attacks, not only in the course of the devastating riots during the Pride Parade 2021. Also then, besides right-wing extremists, high-ranking spiritual dignitaries were in the front line, set the rainbow flag on fire and actively participated in the violence.

Nino Haratischwili processes these impressions in her play Phaedra, in Flames, which is currently on the program of the Vienna Akademietheater, and reacts to them by changing the myth so that Phaedra falls in love with Persea instead of Hippolytus.

In Georgia, her drama, which now centers on a lesbian love affair, could either not be performed or would again be used by far-right supporters and the church as an occasion for new escalations.

In the work The Eighth Life, Haratischwili tells the story of David, who is severely mistreated because of his homosexuality. His sexual orientation is equated by society with child abuse, and for this he must atone.

In the dialogue between David and young Niza, the author uses the innocent views of the girl to illustrate how simple tolerance could work.

“-But why do the others say you are a pederast when you are not? –

-Because most people here use this term incorrectly and you call every homosexual man a pederast because it is a swear word and you classify not only the pederasts but also homosexuals as sick people.

– But then we can continue to see each other if you are not a pederast at all? We just have to explain to them that you like grown men and not children, besides, I’m not a man at all, they’ll understand that, won’t they?” Haratischwili, Nino: The Eighth Life (For Brilka), p. 978.

The love affair between the women Amy, Fred, and Kitty described in the same work can also be understood as a protest against the prevailing intolerance.

Personal thoughts on the work of Nino Haratischwilis Book

Deeply impressed and touched, the novel left me, with wistfulness I closed the book and would have enjoyed too much more than the almost 1300 pages of it.

I have researched many historical and political details, thus dealing more intensively with Georgian history than I had actually planned and thus expanding my knowledge. Haratischwili does not engage in propaganda, but always tries to illuminate both sides of the conflict, so that in the end the reader can form his own unbiased opinion.

The book has awakened my interest in Georgia and is partly responsible for the deep affection I have had for the country and its people since my trips to Tbilisi. Moreover, it was explained to me very clearly why Georgians are the way they are. The behind-the-scenes view gained in this way was a plus as a tourist in Tbilisi and helped me not to judge too hastily.

The author’s linguistic expressiveness is remarkable, all the more so because she does not express herself in her native language. As someone who, despite all the difficulties, still hasn’t given up learning Georgian, I know how different the two languages are and admire Haratishvili’s artfully arranged words all the more. Some of the descriptions of violence and humiliation are painful just to read, and they are meant to be. The author wants to make it as uncomfortable as possible for the reader, who sits sheltered and protected in the well-tempered living room at home, to shake him up and raise his awareness of the atrocities of the past.

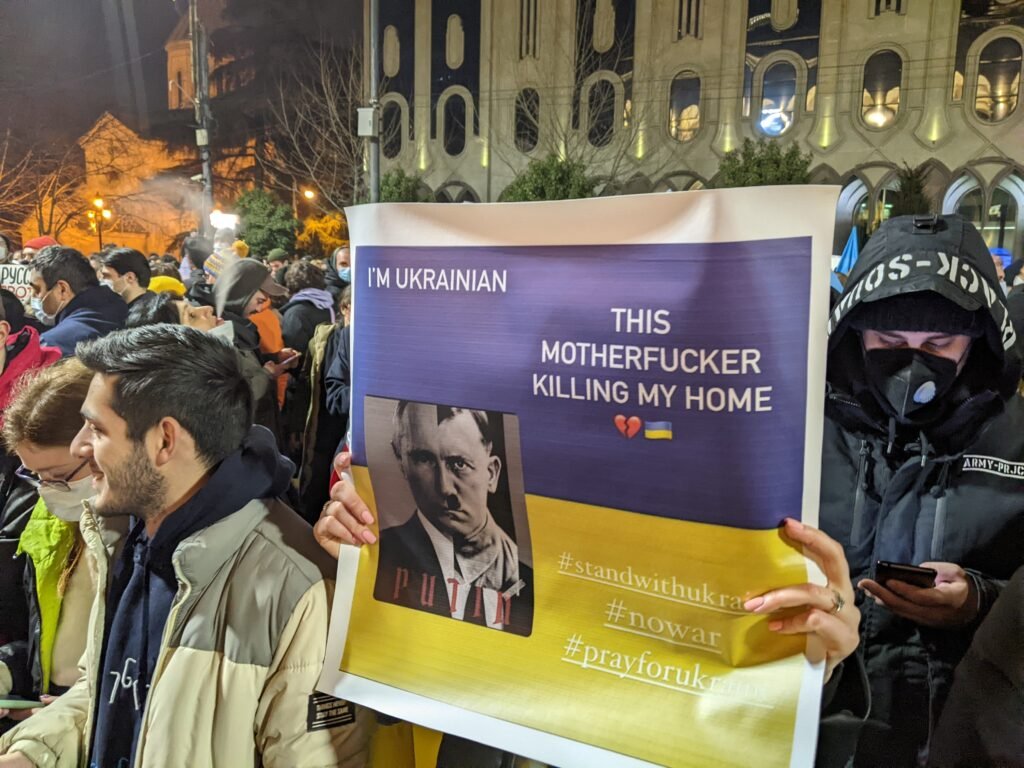

I was also deeply impressed by how consciously Haratischwili uses her power to draw attention to injustices. Unfortunately, unlike in her novel The Eighth Life, it is not possible to bring about change and healing through art alone. The author writes “against forgetting”, history repeats itself, only the victims are different. Especially with Ukraine in mind, it is more important than ever that as many people as possible remember. Haratischwili also draws attention to the prevailing imbalance in the portrayal of history, which is largely left to the West. There were and are far too few people from the East who make themselves heard publicly, which is why she takes her responsibility all the more seriously and directly contrasts the wars in Georgia with the Holocaust in her novel.

Like Hitler, Stalin systematically extinguished human lives, it is estimated that his purges killed up to 60 million people, he was also a dictator. But this fact has not been given enough attention by the West, which, in her opinion, has led to a massive underestimation in Western countries not only of Stalin, but also of Russia. It seems that Europe has still not managed to assess things correctly. Otherwise, there would be no doubt that Putin’s genocide in Ukraine is a seamless continuation of the Holocaust, following in the footsteps of Stalin and Hitler.